In my last post, I began talking about the fundamental difference in the understanding of the proper use of topspin in today’s modern power tennis between US tennis and the rest of the successful tennis nations (i.e. Spain, France, Argentina, etc.).

The “rest of the tennis world” understands topspin as:

“Topspin” = “Control”.

Whereas, here in the US, the powers and coaches understand topspin as:

“Topspin” = “Slowing the ball down”.

Therefore, the “rest of the world” has been teaching their players how to maximize control at ever-increasing ball speeds that we see in today’s top-level tennis, and here in the US, we are developing players whose strokes become inconsistent, unstable and uncontrollable at those same speeds…

And you wonder why US tennis has trouble consistently producing legitimate (ATP) Top 100 prospects?

Who in the US pro tennis pipeline possesses the technical profile of a true Top 100, much less Top 50 ATP pro—i.e. a player with excellent foot speed, who can consistently hit first serves over 125 MPH, and has today’s super-heavy, high-speed topspin groundstrokes?

Well, at least there’s one US player who fits this profile and his name is Donald Young (ATP #98).

Is there anyone else?

The answer is not really… What we have is a tiny smattering of players who have one or two of the required attributes above, but it’s just not in the right combination to give me any reason to foresee a Top 30 or Top 50 future for them. Physical superiority cancels out all theory, and our “prospects” simply fall short on the physical and technical side of things these days.

For example, there are some US players who fulfill the 125+ MPH serve part, but not the heavy groundstroke part, nor the speedy footwork part (i.e. Isner, Delic, and Kendrick), and some who have the heavy groundstrokes but not the foot speed nor supersonic serve (i.e. Kuznetsov), etc. Is there an up-and-comer who at least has the foot speed/heavy topspin groundstroke profile other than Young? Maybe Jesse Levine, but he first needs to generate at least another 10 to 15 MPH on both his first and second serves.

So to close out this part of our discussion, is there anything we can do about the scarcity of legitimate US tennis prospects?

Well, having now met many of those in charge of US high-performance tennis, I’d say there’s not much anyone can do to change this situation really, unless we start hiring coaches and trainers from outside US tennis. The knowledge level of the principals of the US tennis establishment today is simply too dated and therefore inferior to be useful today or for the future. And since we haven’t yet perfected time travel, the only solution is to (reluctantly) admit that we lack modern tennis knowledge and begin hiring those outside experts from Spain, France and elsewhere.

You know that’s not going to happen anytime soon, so expect the prospect drought to continue.

Sorry about the slight drift off-topic, but the more I observe here in our fallen tennis nation, I feel more disappointed than encouraged ...

Back to the subject at hand, and let's continue our on-going conversation about the proper use of topspin…

So, the first thing you need to understand about topspin today, is that topspin is a(n) (technical) attribute that must be maximized in today’s high-performance tennis. Maximize topspin production on your groundstrokes (and serves, for that matter), and by definition, you are maximizing your ability to control your shots.

This fact is especially true given the ball speeds that top players today can consistently generate on their strokes. We have measured groundstroke speeds well over 100 MPH that are struck in the regular course of matchplay at the pro level, where the average rally speed is consistently in the mid-80 MPH range (it was in the low-to-mid 70s for the most part up to about 2002 or 2003). The only way to control the length and placement over such high-speed strokes, maybe the only way to keep the ball in play, is to maximize the amount of topspin applied to each stroke.

The topspin rates on today’s strokes are also higher than they’ve ever been as well, as topspin production increases in direct proportion with increasing overall racket and ball speeds, and especially given the techniques used by players today to strike their shots.

So, how do you strike the ball to maximize both straight-ahead ball speed and the topspin to control all that speed?

There are two crucial elements to today’s maximum topspin groundstrokes:

First, contact is made with a slightly closed racket face (anywhere from 3 to 10 degrees closed; and the racket face is closed throughout the entire forehand movement for most top ATP pros);

AND

Second, the overall swing path is considerable shallower (by almost 50% or more in many cases) than the swing path used in the past to generate heavy topspin.

The Federer forehand is representative of this “new topspin”, where he maintains a very closed racket face at all stages of his forehand stroke—from the backswing, through impact and during the follow-through—as well as swinging his racket on a path that is only about 30 degrees upward from start to finish such that rarely does his racket finish higher than his shoulder line. The result of this “swing geometry” is an extremely high-speed, high-spin stroke that flies through the air with the trajectory of a stroke with a much lower spin rate—i.e. the trajectory of what’s understood to be representative of a “flat” groundstroke.

Previous incarnations of the heavy topspin forehand involved both a far less extreme closure of the racket face (a perfectly perpendicular racket face was considered to be optimal), and a much steeper—anywhere from 45 to 60 degrees upward versus 30 degrees—overall swing path. What also needs to be mentioned here is that the racket speeds used in the past were also significantly slower than those used today, and the only way to hit groundstrokes that landed deep in the court with heavy topspin was to employ the “swing geometry” described above.

If you try to use the same swing geometry as the “classic” heavy topspin forehand to achieve today’s ball speeds (i.e. 85 to 95 MPH), I can almost guarantee you that every shot you hit using the “classic” geometry would fly well beyond the lines of the court. You cannot generate enough topspin with the “classic” topspin stroke mechanics to control the shot trajectory that results from making contact with such high racket speeds.

I have been a frustrated first-hand witness to this physical reality as one of my own players insists on relying on his “classic” heavy topspin forehand mechanics… Despite the fact that he can only put between 50 to 60% of his forehands into the court in a no-pressure, fed-ball drill when he tries to strike the ball over a certain speed using his current “classic” mechanics.

I concede that at this point, my conclusions about the differences between the “modern”, Federer-type swing and impact geometries or the “classic”, Borg/Lendl-type geometries, are based for the most part on anecdotal information, and not on discrete measurements of their actual “geometries” in terms of degrees and MPH. I have only limited measurement data of these attributes and let me say that even acquiring those measurements is a daunting (financial and “cultural”) challenge that involves pricey (to say the least) high-speed video and Doppler radar technologies.

However, I can say that I am very interested in getting this information because I think it has tremendous value in systematically teaching players the type of swing mechanics that will enable them to generate the kind of strokes that are required to be truly competitive at the pro level today and in the future. And, let me say that few of my colleagues and I have already launched an effort to collect this information, so stay tuned…

Let me close out this post by discussing my keen interest in, and dismay about the overall lack of interest on the part of the tennis coaches in the physics of tennis—especially when it comes to measuring the physical attributes of a tennis ball flying off of the string bed of a tennis racket swung by a live human being. There is no readily available information or, it seems, interest on the part of the vast majority of tennis coaches on knowing and understanding, much less teaching the proper launch and impact conditions of tennis strokes.

Contrast the apparent disinterest of the tennis crowd with tennis “ballistics” with the nearly obsessive-compulsive concern of the typical pro (and recreational)golfer with the launch conditions, swing geometries and impact physics of their 14 or more different clubs with their specific model of golf ball that they use during for competition. On the other hand, if someone is interested in performing at the “ultimate level”, isn’t it logical that they (the athlete him/herself) would be very uncomfortable and unsettled to hear from their coaches that a such detailed level of understanding of the very skills they need to have to be competitive with the best of the best is “unnecessary”.

Extreme as it sounds, I think it’s normal for a professional athlete and their coaches and trainers to know and understand as much as possible about the attributes of the skills required to produce a performance level that enables them to be truly competitive at the highest echelons of their chosen sport.

That the tennis crowd largely doesn’t care to know, or worse, believes that this level of understanding is somehow unnecessary to improving the skills of all players who enjoy this great sport is somehow disappointing and disillusioning. But given the reality that the vast majority of tennis knowledge circulating today is based solely on anecdotal information, why would anyone in tennis even bother to care about understanding the game using authentically objective information?

TTFN!

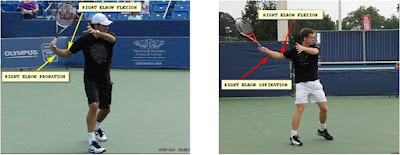

P.S. Note that I’ve omitted any mention of the “double-bend structure” that is commonly touted by so-called tennis experts as a fundamental element of their conception of the modern forehand…

Why is this?

It’s because, IMHO, the “double-bend structure” is a mechanical flaw that emerges naturally to compensate for less-than-optimal positioning relative to ball contact (and is itself justified and reinforced by another myth of “classic” tennis instruction that’s commonly used by the coaching establishment that usually comes out as “crowd the ball for more power”). Let’s put it this way, if you do possess authentic, Federer-ian forehand mechanics, you need to disrupt the double-bend structure to reproduce what Roger is actually doing.

I think my friend puts it best: “double-bend” = “double confusion”.

I mainly see the “double-bend structure” as another flawed variation on the modern forehand.

Anyway, we’ll return to this subject in a future post.

Labels: ATP, classic tennis technique, Donald Young, double bend structure, Federer forehand, high performance tennis, Jesse Levine, launch conditions, modern forehand technique, Roger Federer, US tennis